Michael Faraday

English text see below

Michael Faraday, el famoso físico. Su dicho más conocido

fue: "Nada es demasiado increíble

para ser verdad", al parecer no estaba destinado para aplicarse a las

mesas giratorias, era demasiado increíble, incluso para él. Su teoría sobre los

movimientos de las mesas decía que eran causados por presiones musculares

inconscientes y fue presentado por primera vez en The Times, el 30 de junio de 1853. Para demostrarlo preparó dos

tablillas planas de unas pocas pulgadas cuadradas colocando varios rodillos de

vidrio entre ellas y sujeto todo con un par de bandas de goma elástica, de tal

manera que la parte superior deslizaba sobre la de abajo cuando había una

presión lateral sobre la parte superior. Un índice claro fue fijado en la parte

superior que revelaría el menor movimiento. Y se movió. Se demostró que los

dedos se deslizaban pero la mesa no. Faraday también descubrió que cuando los

asistentes aprendieron el significado del índice mantuvieron su atención fija

en él y ningún movimiento se produjo.

Sin embargo, la presión de las manos era insignificante y

prácticamente neutralizada por la ausencia de dirección unánime. Los asistentes

no deseaban el mismo movimiento en ese mismo momento.

Por esta razón y por otra de más peso como el movimiento de

las mesas sin contacto, su teoría pronto se fue por la borda. Según el

catedrático Richet, fue Chevreul, el famoso químico francés quien originalmente

desarrolló la hipótesis de la presión muscular inconsciente. El libro de

Chevreul, sin embargo, no fue publicado hasta 1854, un año después de la

explicación de Faraday.

En años posteriores se hicieron muchos intentos para demostrar a Faraday la realidad de los fenómenos psíquicos. Él fue demasiado obstinado. "Los que dicen que son testigos de esas cosas no son testigos competentes de los hechos", escribió en 1865. Fue invitado a asistir a la primera sesión con los Hermanos Davenport en su casa de Boucicault, y él devolvió la respuesta: "Si son comunicaciones espirituales, no tienen absolutamente ningún valor, deben pasar a iniciar la actividad, voy a confiar en los espíritus que descubran por sí mismos cómo pueden moverse para cambiar mi atención. Estoy cansado de ellos."

Él fue miembro de una secta religiosa oscura, los

Sandemanianos, que defendían puntos de vista bíblicos rígidos. Cuando Sir

William Crookes le preguntó cómo se concilia la ciencia con la religión, la

respuesta de él fue que la ciencia y la religión están estrictamente separadas.

En la época del juicio Home-Lyon, el catedrático

Tyndall, envió una carta al Pall Mall

Gazette (May 5, 1868), contó la historia de que años antes Faraday hubo

aceptado una invitación para investigar los fenómenos de D. D. Home, pero no se

cumplieron sus condiciones en la investigación y no se concretó la cita. Cuando se publicó la correspondencia original sobre el tema

entre Faraday y Sir Emerson Tennat parecía que una de las condiciones fue:

"Si los efectos son milagrosos o es obra de los espíritus, quien lo hace

(Home) ¿admitirá el carácter absolutamente despreciable, tanto de ellos como de

sus resultados hasta el momento actual con respecto a cualquier información o

instrucción que suministre cualquier fuerza o acción siendo del mínimo valor

para la humanidad?

Robert Bell, el intermediario de la propuesta, encontró la

carta de Faraday tan absurda que sin consultar con Home declinó su

intervención. Cuando Home conoció la carta, se indignó bastante. Faraday no se

hubiera pronunciado en un tono definitivo sobre el espiritualismo si hubiera

recordado la respuesta que él dio a la pregunta: ¿Cuál es uso del descubrimiento de la

inducción", dijo Franklin. ¡El mismo

que un niño que crece hasta ser adulto! El catedrático Tyndall, un escéptico

como una casa elogió la actitud de Faraday, pero este en verdad se encontraba

solo. "La carta, "escribe Podmore en Modern Spiritualism, "fue,

por supuesto, indigna del alto carácter de Faraday y de una eminencia

científica, fue sin duda, el resultado

de un momento de irritación transitoria. La posición adoptada fue bastante

indefendible. Para entrar en la investigación sobre el tema eligió un juego que

sin duda era una parodia de los métodos científicos."

En una serie de sesiones entre 1888-1910, en el Spring Hall,

Kansas, el espíritu que presidía decía ser Faraday. Sus comunicaciones fueron

publicadas en cuatro libros, Rending of the Veil; Beyond the Veil; The Guiding

Star y The Dawn of Another Life.

Enciclopedia de Ciencias Psíquicas - Nandor Fodor

*******************************

FARADAY,

MICHAEL, the

famous physicist. His well-known saying: "Nothing is too amazing to be

true" apparently was not meant to cover tableturning. It was, for him, too

amazing to be true. His noted theory that table movements were caused by

unconscious muscular pressure was first put forward in a letter to The Times

of June 30, 1853. To prove it he prepared two small flat boards a few

inches square, placed several glass rollers between them and fastened the whole

together with a couple of indiarubber bands in such a manner that the upper

board would slide under lateral pressure to a limited extent over the lower

one. A light index fastened to the upper board would betray the least sliding.

It did betray. The upper board always moved first, which demonstrated that the

fingers moved the table and not the table the fingers. Faraday also found that

when the sitters learned the meaning of the index and kept their attention

fixed on it, no movement took place. When it was hidden from their sight it

kept on wavering, though the sitters believed that they always pressed directly

downward. However, the pressure of the hands was trifling and was practically

neutralised by the absence of unanimity in the direction. The sitters never

desired the same movement at the same moment.

For this reason, and for the still

weightier one that tables moved without contact as well, his theory soon went

overboard. According to Prof. Richet it was Chevreul, the famous French

chemist, who originally evolved the theory of unconscious muscular pressure.

Chevreul's book, however, did not appear until 1854, a year after Faraday's

explanation was published.

In later years many attempts were made

to prove to Faraday the reality of psychic phenomena. He was too obstinate.

"They who say these things are not competent witnesses of facts," he

wrote in 1865. To an invitation to attend the first seance of the Davenport

Brothers in Boucicault's house he returned the answer: "If spirit

communications, not utterly worthless, should happen to start into activity, I

will trust the spirits to find out for themselves how they can move my

attention. I am tired of them." He was a member of an obscure religious

sect, the Sandemanians holding rigid Biblical views. When Sir William Crookes

inquired how he reconciled science with religion, he received the reply that he

kept his science and religion strictly apart.

At the time of the Home-Lyon trial

Professor Tyndall, in a letter in Pall Mall Gazette (May 5, 1868), told

the story that years before Faraday had accepted an invitation to examine the

phenomena of D. D. Home but his conditions were not met with and the

investigation fell through. When the original correspondence on the subject between

Faraday and Sir Emerson Tennant was published it appeared that one of Faraday's

conditions was: "If the effects are miracles, or the work of spirits, does

he (Home) admit the utterly contemptible character, both of them and their

results, up to the present time, in respect either of yielding information or

instruction or supplying any force or action of the least value to

mankind?" Robert Bell, the intermediary for the proposed seance, found

Faraday's letter so preposterous that, without consulting Home, he declined his

intervention. Home, when he learned about it, was duly indignant. Faraday may

not have pronounced in a tone of such finality about spiritualism had he

remembered the answer which he returned to the question: what is the use of the

discovery of induction? He quoted Franklin "What is the use of a child -

it grows to be a man!"I Professor Tyndall, as an arch sceptic, commended

Faraday's attitude, but in this he was alone. "The letter," writes

Podmore in Modern Spiritualism, "was, of course, altogether

unworthy of Faraday's high character and scientific eminence, and was no doubt

the outcome of a moment of transient irritation. The position taken was quite

indefensible. To enter upon a judicial inquiry by treating the subject-matter

as a chose jugée was surely a parody of scientific methods."

In a series of seances between

1888-1910 in Spring Hall, Kansas, the presiding spirit claimed to be Faraday.

His communications were published in four books: Rending of the Veil; Beyond

the Veil; The Guiding Star and The Dawn of Another Life.

Michel Eugène Chevreul

William Crookes

John Tyndall

Sir James Emerson Tennent

Robert Bell

Médium Daniel Dunglas Home

Los hermanos Davenport, Sr. Fay y Sr. Cooper

1853 - Sesión de mesa giratoria.

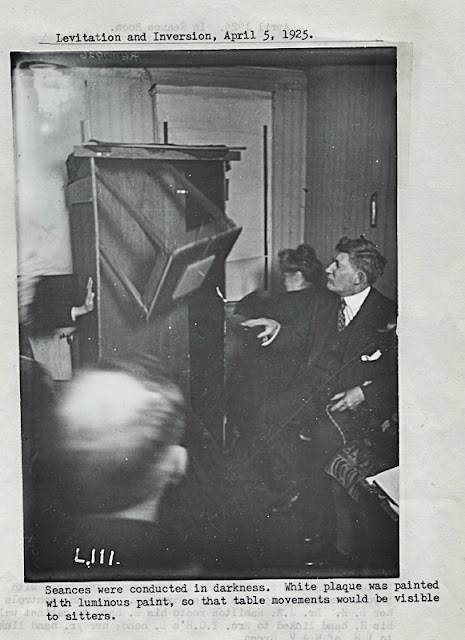

Levitación de la mesa sin contacto - "The Hamilton Files" (Walter Falk)